THIS BLOG IS FOR THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE RIZAL SUBJECT STUDENTS OF CSCJ UNDER THE SUBJECT TEACHER WHOSE WISH IS TO MAKE HIS STUDENTS RIZAL-LIKE IN THEIR ACHIEVEMENTS AND DETERMINATION IN LIFE! MISS IT AND YOU'LL BE RISKING YOURSELF EXECUTION BY FIRING SQUAD!

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

GOOD LUCK TO YOU IN YOUR PRELIM EXAMS!

TOMORROW will be the HED's Christmas party. The two days that follow will be the prelim examinations. And another day on the 4th of January.

GOOD LUCK! study well....

God bless!

GO, get that EXCELLENT rating! Just like you are eating PEANUTS!

MERRY CHRISTMAS and a HAPPY NEW YEAR to you and to your family!

ANG BUHAY NG ISANG BAYANI

We have discussed in passing Chapter 1 of the textbook we are using in the study of Rizal (His Life, Works and Writings).

In addition, was our viewing of the Documentary film (Ateneo Media Center) on his Life entitled JOSE RIZAL: ANG BUHAY NG ISANG BAYANI.

And so, here's a more comprehensive look at his biography.

The following article is taken from the site: http://joserizal.ph/

Jose Rizal: A Biographical Sketch

BY TEOFILO H. MONTEMAYOR

JOSE RIZAL, the national hero of the Philippines and pride of the Malayan race, was born on June 19, 1861, in the town of Calamba, Laguna. He was the seventh child in a family of 11 children (2 boys and 9 girls). Both his parents were educated and belonged to distinguished families.

His father, Francisco Mercado Rizal, an industrious farmer whom Rizal called "a model of fathers," came from Biñan, Laguna; while his mother, Teodora Alonzo y Quintos, a highly cultured and accomplished woman whom Rizal called "loving and prudent mother," was born in Meisic, Sta. Cruz, Manila. At the age of 3, he learned the alphabet from his mother; at 5, while learning to read and write, he already showed inclinations to be an artist. He astounded his family and relatives by his pencil drawings and sketches and by his moldings of clay. At the age 8, he wrote a Tagalog poem, "Sa Aking Mga Kabata," the theme of which revolves on the love of one’s language. In 1877, at the age of 16, he obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree with an average of "excellent" from the Ateneo Municipal de Manila. In the same year, he enrolled in Philosophy and Letters at the University of Santo Tomas, while at the same time took courses leading to the degree of surveyor and expert assessor at the Ateneo. He finished the latter course on March 21, 1877 and passed the Surveyor’s examination on May 21, 1878; but because of his age, 17, he was not granted license to practice the profession until December 30, 1881. In 1878, he enrolled in medicine at the University of Santo Tomas but had to stop in his studies when he felt that the Filipino students were being discriminated upon by their Dominican tutors. On May 3, 1882, he sailed for Spain where he continued his studies at the Universidad Central de Madrid. On June 21, 1884, at the age of 23, he was conferred the degree of Licentiate in Medicine and on June 19,1885, at the age of 24, he finished his course in Philosophy and Letters with a grade of "excellent."

Having traveled extensively in Europe, America and Asia, he mastered 22 languages. These include Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, English, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Latin, Malayan, Portuguese, Russian, Sanskrit, Spanish, Tagalog, and other native dialects. A versatile genius, he was an architect, artists, businessman, cartoonist, educator, economist, ethnologist, scientific farmer, historian, inventor, journalist, linguist, musician, mythologist, nationalist, naturalist, novelist, opthalmic surgeon, poet, propagandist, psychologist, scientist, sculptor, sociologist, and theologian.

He was an expert swordsman and a good shot. In the hope of securing political and social reforms for his country and at the same time educate his countrymen, Rizal, the greatest apostle of Filipino nationalism, published, while in Europe, several works with highly nationalistic and revolutionary tendencies. In March 1887, his daring book, NOLI ME TANGERE, a satirical novel exposing the arrogance and despotism of the Spanish clergy, was published in Berlin; in 1890 he reprinted in Paris, Morga’s SUCCESSOS DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS with his annotations to prove that the Filipinos had a civilization worthy to be proud of even long before the Spaniards set foot on Philippine soil; on September 18, 1891, EL FILIBUSTERISMO, his second novel and a sequel to the NOLI and more revolutionary and tragic than the latter, was printed in Ghent. Because of his fearless exposures of the injustices committed by the civil and clerical officials, Rizal provoked the animosity of those in power. This led himself, his relatives and countrymen into trouble with the Spanish officials of the country. As a consequence, he and those who had contacts with him, were shadowed; the authorities were not only finding faults but even fabricating charges to pin him down. Thus, he was imprisoned in Fort Santiago from July 6, 1892 to July 15, 1892 on a charge that anti-friar pamphlets were found in the luggage of his sister Lucia who arrive with him from Hong Kong. While a political exile in Dapitan, he engaged in agriculture, fishing and business; he maintained and operated a hospital; he conducted classes- taught his pupils the English and Spanish languages, the arts.

The sciences, vocational courses including agriculture, surveying, sculpturing, and painting, as well as the art of self defense; he did some researches and collected specimens; he entered into correspondence with renowned men of letters and sciences abroad; and with the help of his pupils, he constructed water dam and a relief map of Mindanao - both considered remarkable engineering feats. His sincerity and friendliness won for him the trust and confidence of even those assigned to guard him; his good manners and warm personality were found irresistible by women of all races with whom he had personal contacts; his intelligence and humility gained for him the respect and admiration of prominent men of other nations; while his undaunted courage and determination to uplift the welfare of his people were feared by his enemies.

When the Philippine Revolution started on August 26, 1896, his enemies lost no time in pressing him down. They were able to enlist witnesses that linked him with the revolt and these were never allowed to be confronted by him. Thus, from November 3, 1986, to the date of his execution, he was again committed to Fort Santiago. In his prison cell, he wrote an untitled poem, now known as "Ultimo Adios" which is considered a masterpiece and a living document expressing not only the hero’s great love of country but also that of all Filipinos. After a mock trial, he was convicted of rebellion, sedition and of forming illegal association. In the cold morning of December 30, 1896, Rizal, a man whose 35 years of life had been packed with varied activities which proved that the Filipino has capacity to equal if not excel even those who treat him as a slave, was shot at Bagumbayan Field.

In addition, was our viewing of the Documentary film (Ateneo Media Center) on his Life entitled JOSE RIZAL: ANG BUHAY NG ISANG BAYANI.

And so, here's a more comprehensive look at his biography.

The following article is taken from the site: http://joserizal.ph/

Jose Rizal: A Biographical Sketch

BY TEOFILO H. MONTEMAYOR

JOSE RIZAL, the national hero of the Philippines and pride of the Malayan race, was born on June 19, 1861, in the town of Calamba, Laguna. He was the seventh child in a family of 11 children (2 boys and 9 girls). Both his parents were educated and belonged to distinguished families.

His father, Francisco Mercado Rizal, an industrious farmer whom Rizal called "a model of fathers," came from Biñan, Laguna; while his mother, Teodora Alonzo y Quintos, a highly cultured and accomplished woman whom Rizal called "loving and prudent mother," was born in Meisic, Sta. Cruz, Manila. At the age of 3, he learned the alphabet from his mother; at 5, while learning to read and write, he already showed inclinations to be an artist. He astounded his family and relatives by his pencil drawings and sketches and by his moldings of clay. At the age 8, he wrote a Tagalog poem, "Sa Aking Mga Kabata," the theme of which revolves on the love of one’s language. In 1877, at the age of 16, he obtained his Bachelor of Arts degree with an average of "excellent" from the Ateneo Municipal de Manila. In the same year, he enrolled in Philosophy and Letters at the University of Santo Tomas, while at the same time took courses leading to the degree of surveyor and expert assessor at the Ateneo. He finished the latter course on March 21, 1877 and passed the Surveyor’s examination on May 21, 1878; but because of his age, 17, he was not granted license to practice the profession until December 30, 1881. In 1878, he enrolled in medicine at the University of Santo Tomas but had to stop in his studies when he felt that the Filipino students were being discriminated upon by their Dominican tutors. On May 3, 1882, he sailed for Spain where he continued his studies at the Universidad Central de Madrid. On June 21, 1884, at the age of 23, he was conferred the degree of Licentiate in Medicine and on June 19,1885, at the age of 24, he finished his course in Philosophy and Letters with a grade of "excellent."

Having traveled extensively in Europe, America and Asia, he mastered 22 languages. These include Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, English, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Latin, Malayan, Portuguese, Russian, Sanskrit, Spanish, Tagalog, and other native dialects. A versatile genius, he was an architect, artists, businessman, cartoonist, educator, economist, ethnologist, scientific farmer, historian, inventor, journalist, linguist, musician, mythologist, nationalist, naturalist, novelist, opthalmic surgeon, poet, propagandist, psychologist, scientist, sculptor, sociologist, and theologian.

He was an expert swordsman and a good shot. In the hope of securing political and social reforms for his country and at the same time educate his countrymen, Rizal, the greatest apostle of Filipino nationalism, published, while in Europe, several works with highly nationalistic and revolutionary tendencies. In March 1887, his daring book, NOLI ME TANGERE, a satirical novel exposing the arrogance and despotism of the Spanish clergy, was published in Berlin; in 1890 he reprinted in Paris, Morga’s SUCCESSOS DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS with his annotations to prove that the Filipinos had a civilization worthy to be proud of even long before the Spaniards set foot on Philippine soil; on September 18, 1891, EL FILIBUSTERISMO, his second novel and a sequel to the NOLI and more revolutionary and tragic than the latter, was printed in Ghent. Because of his fearless exposures of the injustices committed by the civil and clerical officials, Rizal provoked the animosity of those in power. This led himself, his relatives and countrymen into trouble with the Spanish officials of the country. As a consequence, he and those who had contacts with him, were shadowed; the authorities were not only finding faults but even fabricating charges to pin him down. Thus, he was imprisoned in Fort Santiago from July 6, 1892 to July 15, 1892 on a charge that anti-friar pamphlets were found in the luggage of his sister Lucia who arrive with him from Hong Kong. While a political exile in Dapitan, he engaged in agriculture, fishing and business; he maintained and operated a hospital; he conducted classes- taught his pupils the English and Spanish languages, the arts.

The sciences, vocational courses including agriculture, surveying, sculpturing, and painting, as well as the art of self defense; he did some researches and collected specimens; he entered into correspondence with renowned men of letters and sciences abroad; and with the help of his pupils, he constructed water dam and a relief map of Mindanao - both considered remarkable engineering feats. His sincerity and friendliness won for him the trust and confidence of even those assigned to guard him; his good manners and warm personality were found irresistible by women of all races with whom he had personal contacts; his intelligence and humility gained for him the respect and admiration of prominent men of other nations; while his undaunted courage and determination to uplift the welfare of his people were feared by his enemies.

When the Philippine Revolution started on August 26, 1896, his enemies lost no time in pressing him down. They were able to enlist witnesses that linked him with the revolt and these were never allowed to be confronted by him. Thus, from November 3, 1986, to the date of his execution, he was again committed to Fort Santiago. In his prison cell, he wrote an untitled poem, now known as "Ultimo Adios" which is considered a masterpiece and a living document expressing not only the hero’s great love of country but also that of all Filipinos. After a mock trial, he was convicted of rebellion, sedition and of forming illegal association. In the cold morning of December 30, 1896, Rizal, a man whose 35 years of life had been packed with varied activities which proved that the Filipino has capacity to equal if not excel even those who treat him as a slave, was shot at Bagumbayan Field.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

RIZAL'S CHILDHOOD

Source: http://joserizal.ph/

In Calamba, Laguna 19 June 1861

JOSE RIZAL, the seventh child of Francisco Mercado Rizal and Teodora Alonso y Quintos, was born in Calamba, Laguna.

22 June 1861

He was baptized JOSE RIZAL MERCADO at the Catholic of Calamba by the parish priest Rev. Rufino Collantes with Rev. Pedro Casañas as the sponsor.

28 September 1862

The parochial church of Calamba and the canonical books, including the book in which Rizal’s baptismal records were entered, were burned.

1864

Barely three years old, Rizal learned the alphabet from his mother.

1865

When he was four years old, his sister Conception, the eight child in the Rizal family, died at the age of three. It was on this occasion that Rizal remembered having shed real tears for the first time.

1865 – 1867

During this time his mother taught him how to read and write. His father hired a classmate by the name of Leon Monroy who, for five months until his (Monroy) death, taught Rizal the rudiments of Latin.

At about this time two of his mother’s cousin frequented Calamba. Uncle Manuel Alberto, seeing Rizal frail in body, concerned himself with the physical development of his young nephew and taught the latter love for the open air and developed in him a great admiration for the beauty of nature, while Uncle Gregorio, a scholar, instilled into the mind of the boy love for education. He advised Rizal: "Work hard and perform every task very carefully; learn to be swift as well as thorough; be independent in thinking and make visual pictures of everything."

6 June 1868

With his father, Rizal made a pilgrimage to Antipolo to fulfill the vow made by his mother to take the child to the Shrine of the Virgin of Antipolo should she and her child survive the ordeal of delivery which nearly caused his mother’s life.

From there they proceeded to Manila and visited his sister Saturnina who was at the time studying in the La Concordia College in Sta. Ana.

1869

At the age of eight, Rizal wrote his first poem entitled "Sa Aking Mga Kabata." The poem was written in tagalog and had for its theme "Love of One’s Language."

In Biñan, Laguna 1870

His brother Paciano brought Rizal to Biñan, Laguna. He was placed under the tutelage of Justiniano Aquino Cruz, studying Latin and Spanish. In this town he also learned the art of painting under the tutorship of an old painter by the name of Juancho Carrera.

17 December 1870

Having finished his studies in Biñan, Rizal returned to Calamba on board the motorboat Talim. His parents planned to transfer him to Manila where he could continue his studies.

Back in Calamba 1871

His mother was imprisoned in Sta. Cruz, Laguna for allegedly poisoning the wife of her cousin Jose Alberto, a rich property owner of Biñan and brother of Manuel and Gregorio.

1872

For the first time, Rizal heard of the word filibustero which his father forbid the members of his family to utter, including such names as Cavite and Burgos. (It must be remembered that because of the Cavite Mutiny on January 20, 1872, Fathers Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora were garroted at Bagumbayan Field on February 17, 1872.)

In Calamba, Laguna 19 June 1861

JOSE RIZAL, the seventh child of Francisco Mercado Rizal and Teodora Alonso y Quintos, was born in Calamba, Laguna.

22 June 1861

He was baptized JOSE RIZAL MERCADO at the Catholic of Calamba by the parish priest Rev. Rufino Collantes with Rev. Pedro Casañas as the sponsor.

28 September 1862

The parochial church of Calamba and the canonical books, including the book in which Rizal’s baptismal records were entered, were burned.

1864

Barely three years old, Rizal learned the alphabet from his mother.

1865

When he was four years old, his sister Conception, the eight child in the Rizal family, died at the age of three. It was on this occasion that Rizal remembered having shed real tears for the first time.

1865 – 1867

During this time his mother taught him how to read and write. His father hired a classmate by the name of Leon Monroy who, for five months until his (Monroy) death, taught Rizal the rudiments of Latin.

At about this time two of his mother’s cousin frequented Calamba. Uncle Manuel Alberto, seeing Rizal frail in body, concerned himself with the physical development of his young nephew and taught the latter love for the open air and developed in him a great admiration for the beauty of nature, while Uncle Gregorio, a scholar, instilled into the mind of the boy love for education. He advised Rizal: "Work hard and perform every task very carefully; learn to be swift as well as thorough; be independent in thinking and make visual pictures of everything."

6 June 1868

With his father, Rizal made a pilgrimage to Antipolo to fulfill the vow made by his mother to take the child to the Shrine of the Virgin of Antipolo should she and her child survive the ordeal of delivery which nearly caused his mother’s life.

From there they proceeded to Manila and visited his sister Saturnina who was at the time studying in the La Concordia College in Sta. Ana.

1869

At the age of eight, Rizal wrote his first poem entitled "Sa Aking Mga Kabata." The poem was written in tagalog and had for its theme "Love of One’s Language."

In Biñan, Laguna 1870

His brother Paciano brought Rizal to Biñan, Laguna. He was placed under the tutelage of Justiniano Aquino Cruz, studying Latin and Spanish. In this town he also learned the art of painting under the tutorship of an old painter by the name of Juancho Carrera.

17 December 1870

Having finished his studies in Biñan, Rizal returned to Calamba on board the motorboat Talim. His parents planned to transfer him to Manila where he could continue his studies.

Back in Calamba 1871

His mother was imprisoned in Sta. Cruz, Laguna for allegedly poisoning the wife of her cousin Jose Alberto, a rich property owner of Biñan and brother of Manuel and Gregorio.

1872

For the first time, Rizal heard of the word filibustero which his father forbid the members of his family to utter, including such names as Cavite and Burgos. (It must be remembered that because of the Cavite Mutiny on January 20, 1872, Fathers Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora were garroted at Bagumbayan Field on February 17, 1872.)

THE SAGRADISTA "RIZALISTS"

Who said you can run away from taking the RIZAL subject?

ONLY in your dream, your WILDEST of dreams!

First off, it's because RIZAL is a mandated subject. Republic Act 1425 (R.A. 1425) prescribes the teaching of RIZAL's LIFE, WORKS and WRITINGS in ALL schools, Colleges and Universities. ALL tertiary level students then, whether taking a two-year course or a Bachelor degree has to take the subject. PERIOD!

Well, i know fully well, you want to graduate.

And that's WHY we MEET!

Any questions, class?

There, being none... let us all stand for the prayer.

ONLY in your dream, your WILDEST of dreams!

First off, it's because RIZAL is a mandated subject. Republic Act 1425 (R.A. 1425) prescribes the teaching of RIZAL's LIFE, WORKS and WRITINGS in ALL schools, Colleges and Universities. ALL tertiary level students then, whether taking a two-year course or a Bachelor degree has to take the subject. PERIOD!

Well, i know fully well, you want to graduate.

And that's WHY we MEET!

Any questions, class?

There, being none... let us all stand for the prayer.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

RETRACTION LETTER/LETTERS (FINALs COVERAGE included)

RIZAL'S RETRACTION

Introduction

This section presents contrasting views on the retraction by biographers of Rizal. The team deemed it proper to present the views in the exact words of the scholars so as to avoid misinterpretations.

Read on and judge for yourself whether Rizal retracted or not.

Texts of Rizal's Retraction

The "original" discovered by Fr. Manuel Garcia, C.M. on May 18, 1935

Me declaro catolica y en esta Religion en que naci y me eduque quiero vivir y morir.

Me retracto de todo corazon de cuanto en mis palabras, escritos, inpresos y conducta ha habido contrario a mi cualidad de hijo de la Iglesia Catolica. Creo y profeso cuanto ella enseña y me somento a cuanto ella manda. Abomino de la Masonaria, como enigma que es de la Iglesia, y como Sociedad prohibida por la Iglesia. Puede el Prelado Diocesano, como Autoridad Superior Eclesiastica hacer publica esta manifastacion espontanea mia para reparar el escandalo que mis actos hayan podido causar y para que Dios y los hombers me perdonen.

Manila 29 de Deciembre de 1896

Jose Rizal

Jefe del Piquete

Juan del Fresno

Ayudante de Plaza

Eloy Moure

Translation (English)

I declare myself a catholic and in this Religion in which I was born and educated I wish to live and die.

I retract with all my heart whatever in my words, writings, publications and conduct has been contrary to my character as son of the Catholic Church. I believe and I confess whatever she teaches and I submit to whatever she demands. I abominate Masonry, as the enemy which is of the Church, and as a Society prohibited by the Church. The Diocesan Prelate may, as the Superior Ecclesiastical Authority, make public this spontaneous manifestation of mine in order to repair the scandal which my acts may have caused and so that God and people may pardon me.

Manila 29 of December of 1896

Jose Rizal

La Voz Española, December 30, 1896

Me declaro catolica y en esta Religion en que naci y me eduque quiero vivir y morir.

Me retracto de todo corazon de cuanto en mis palabras, escritos, inpresos y conducta ha habido contrario a mis cualidades de hijo de la Iglesia Catolica. Creo y profeso cuanto ella enseña y me somento a cuanto ella manda. Abomino de la Masonaria, como enigma que es de la Iglesia y como sociedad prohibida por la Iglesia. Puede el Prelado Diocesano, como autoridad superior eclesiastica hacer publica esta manifastacion espontanea para reparar el escandalo que mis actos hayan podido causar y para que Dios y los hombers me perdonen.

Manila, 29 de Diciembre de

1896-Jose Rizal

Jefe del Piquete

Juan del Fresno

Ayudante de Plaza

Eloy Moure

Fr. Balaguer's text, January 1897

Me declaro catolica y en esta Religion en que naci y me eduque quiero vivir y morir. Me retracto de todo corazon de cuanto en mis palabras, escritos, inpresos y conducta ha habido contrario a mi calidad de hijo de la Iglesia. Creo y profeso cuanto ella enseña y me somento a cuanto Ella manda. Abomino de la Masonaria, como enigma que es de la Iglesia, y como Sociedad prohibida por la misma Iglesia.

Puede el Prelado diocesano, como Autoridad superior eclesiastica hacer publica esta manifastacion espontanea mia, para reparar el escandalo que mis actos hayan podido causar, y para que Dios y los hombers me perdonen.

Manila, 29 de Diciembre de

1896-Jose Rizal

ANALYSIS OF RIZAL'S RETRACTION

At least four texts of Rizal’s retraction have surfaced. The fourth text appeared in El Imparcial on the day after Rizal’s execution; it is the short formula of the retraction.

The first text was published in La Voz Española and Diaro de Manila on the very day of Rizal’s execution, Dec. 30, 1896. The second text appeared in Barcelona, Spain, on February 14, 1897, in the fortnightly magazine in La Juventud; it came from an anonymous writer who revealed himself fourteen years later as Fr. Balaguer. The "original" text was discovered in the archdiocesan archives on May 18, 1935, after it disappeared for thirty-nine years from the afternoon of the day when Rizal was shot.

We know not that reproductions of the lost original had been made by a copyist who could imitate Rizal’s handwriting. This fact is revealed by Fr. Balaguer himself who, in his letter to his former superior Fr. Pio Pi in 1910, said that he had received "an exact copy of the retraction written and signed by Rizal. The handwriting of this copy I don’t know nor do I remember whose it is. . ." He proceeded: "I even suspect that it might have been written by Rizal himself. I am sending it to you that you may . . . verify whether it might be of Rizal himself . . . ." Fr. Pi was not able to verify it in his sworn statement.

This "exact" copy had been received by Fr. Balaguer in the evening immediately preceding Rizal’s execution, Rizal y su Obra, and was followed by Sr. W. Retana in his biography of Rizal, Vida y Escritos del Jose Rizal with the addition of the names of the witnesses taken from the texts of the retraction in the Manila newspapers. Fr. Pi’s copy of Rizal’s retraction has the same text as that of Fr. Balaguer’s "exact" copy but follows the paragraphing of the texts of Rizal’s retraction in the Manila newspapers.

Regarding the "original" text, no one claimed to have seen it, except the publishers of La Voz Espanola. That newspaper reported: "Still more; we have seen and read his (Rizal’s) own hand-written retraction which he sent to our dear and venerable Archbishop…" On the other hand, Manila pharmacist F. Stahl wrote in a letter: "besides, nobody has seen this written declaration, in spite of the fact that quite a number of people would want to see it. "For example, not only Rizal’s family but also the correspondents in Manila of the newspapers in Madrid, Don Manuel Alhama of El Imparcial and Sr. Santiago Mataix of El Heraldo, were not able to see the hand-written retraction.

Neither Fr. Pi nor His Grace the Archbishop ascertained whether Rizal himself was the one who wrote and signed the retraction. (Ascertaining the document was necessary because it was possible for one who could imitate Rizal’s handwriting aforesaid holograph; and keeping a copy of the same for our archives, I myself delivered it personally that the same morning to His Grace Archbishop… His Grace testified: At once the undersigned entrusted this holograph to Rev. Thomas Gonzales Feijoo, secretary of the Chancery." After that, the documents could not be seen by those who wanted to examine it and was finally considered lost after efforts to look for it proved futile.

On May 18, 1935, the lost "original" document of Rizal’s retraction was discovered by the archdeocean archivist Fr. Manuel Garcia, C.M. The discovery, instead of ending doubts about Rizal’s retraction, has in fact encouraged it because the newly discovered text retraction differs significantly from the text found in the Jesuits’ and the Archbishop’s copies. And, the fact that the texts of the retraction which appeared in the Manila newspapers could be shown to be the exact copies of the "original" but only imitations of it. This means that the friars who controlled the press in Manila (for example, La Voz Española) had the "original" while the Jesuits had only the imitations.

We now proceed to show the significant differences between the "original" and the Manila newspapers texts of the retraction on the one hand and the text s of the copies of Fr. Balaguer and F5r. Pio Pi on the other hand.

First, instead of the words "mi cualidad" (with "u") which appear in the original and the newspaper texts, the Jesuits’ copies have "mi calidad" (without "u").

Second, the Jesuits’ copies of the retraction omit the word "Catolica" after the first "Iglesias" which are found in the original and the newspaper texts.

Third, the Jesuits’ copies of the retraction add before the third "Iglesias" the word "misma" which is not found in the original and the newspaper texts of the retraction.

Fourth, with regards to paragraphing which immediately strikes the eye of the critical reader, Fr. Balaguer’s text does not begin the second paragraph until the fifth sentences while the original and the newspaper copies start the second paragraph immediately with the second sentences.

Fifth, whereas the texts of the retraction in the original and in the manila newspapers have only four commas, the text of Fr. Balaguer’s copy has eleven commas.

Sixth, the most important of all, Fr. Balaguer’s copy did not have the names of the witnesses from the texts of the newspapers in Manila.

In his notarized testimony twenty years later, Fr. Balaguer finally named the witnesses. He said "This . . .retraction was signed together with Dr. Rizal by Señor Fresno, Chief of the Picket, and Señor Moure, Adjutant of the Plaza." However, the proceeding quotation only proves itself to be an addition to the original. Moreover, in his letter to Fr. Pi in 1910, Fr. Balaguer said that he had the "exact" copy of the retraction, which was signed by Rizal, but her made no mention of the witnesses. In his accounts too, no witnesses signed the retraction.

How did Fr. Balaguer obtain his copy of Rizal’s retraction? Fr. Balaguer never alluded to having himself made a copy of the retraction although he claimed that the Archbishop prepared a long formula of the retraction and Fr. Pi a short formula. In Fr. Balaguer’s earliest account, it is not yet clear whether Fr. Balaguer was using the long formula of nor no formula in dictating to Rizal what to write. According to Fr. Pi, in his own account of Rizal’s conversion in 1909, Fr. Balaguer dictated from Fr. Pi’s short formula previously approved by the Archbishop. In his letter to Fr. Pi in 1910, Fr. Balaguer admitted that he dictated to Rizal the short formula prepared by Fr. Pi; however; he contradicts himself when he revealed that the "exact" copy came from the Archbishop. The only copy, which Fr. Balaguer wrote, is the one that appeared ion his earliest account of Rizal’s retraction.

Where did Fr. Balaguer’s "exact" copy come from? We do not need long arguments to answer this question, because Fr. Balaguer himself has unwittingly answered this question. He said in his letter to Fr. Pi in 1910:

"…I preserved in my keeping and am sending to you the original texts of the two formulas of retraction, which they (You) gave me; that from you and that of the Archbishop, and the first with the changes which they (that is, you) made; and the other the exact copy of the retraction written and signed by Rizal. The handwriting of this copy I don’t know nor do I remember whose it is, and I even suspect that it might have been written by Rizal himself."

In his own word quoted above, Fr. Balaguer said that he received two original texts of the retraction. The first, which came from Fr. Pi, contained "the changes which You (Fr. Pi) made"; the other, which is "that of the Archbishop" was "the exact copy of the retraction written and signed by Rizal" (underscoring supplied). Fr. Balaguer said that the "exact copy" was "written and signed by Rizal" but he did not say "written and signed by Rizal and himself" (the absence of the reflexive pronoun "himself" could mean that another person-the copyist-did not). He only "suspected" that "Rizal himself" much as Fr. Balaguer did "not know nor ... remember" whose handwriting it was.

Thus, according to Fr. Balaguer, the "exact copy" came from the Archbishop! He called it "exact" because, not having seen the original himself, he was made to believe that it was the one that faithfully reproduced the original in comparison to that of Fr. Pi in which "changes" (that is, where deviated from the "exact" copy) had been made. Actually, the difference between that of the Archbishop (the "exact" copy) and that of Fr. Pi (with "changes") is that the latter was "shorter" be cause it omitted certain phrases found in the former so that, as Fr. Pi had fervently hoped, Rizal would sign it.

According to Fr. Pi, Rizal rejected the long formula so that Fr. Balaguer had to dictate from the short formula of Fr. Pi. Allegedly, Rizal wrote down what was dictated to him but he insisted on adding the phrases "in which I was born and educated" and "[Masonary]" as the enemy that is of the Church" – the first of which Rizal would have regarded as unnecessary and the second as downright contrary to his spirit. However, what actually would have happened, if we are to believe the fictitious account, was that Rizal’s addition of the phrases was the retoration of the phrases found in the original which had been omitted in Fr. Pi’s short formula.

The "exact" copy was shown to the military men guarding in Fort Santiago to convince them that Rizal had retracted. Someone read it aloud in the hearing of Capt. Dominguez, who claimed in his "Notes’ that Rizal read aloud his retraction. However, his copy of the retraction proved him wrong because its text (with "u") and omits the word "Catolica" as in Fr. Balaguer’s copy but which are not the case in the original. Capt. Dominguez never claimed to have seen the retraction: he only "heard".

The truth is that, almost two years before his execution, Rizal had written a retraction in Dapitan. Very early in 1895, Josephine Bracken came to Dapitan with her adopted father who wanted to be cured of his blindness by Dr. Rizal; their guide was Manuela Orlac, who was agent and a mistress of a friar. Rizal fell in love with Josephine and wanted to marry her canonically but he was required to sign a profession of faith and to write retraction, which had to be approved by the Bishop of Cebu. "Spanish law had established civil marriage in the Philippines," Prof. Craig wrote, but the local government had not provided any way for people to avail themselves of the right..."

In order to marry Josephine, Rizal wrote with the help of a priest a form of retraction to be approved by the Bishop of Cebu. This incident was revealed by Fr. Antonio Obach to his friend Prof. Austin Craig who wrote down in 1912 what the priest had told him; "The document (the retraction), inclosed with the priest’s letter, was ready for the mail when Rizal came hurrying I to reclaim it." Rizal realized (perhaps, rather late) that he had written and given to a priest what the friars had been trying by all means to get from him.

Neither the Archbishop nor Fr. Pi saw the original document of retraction. What they was saw a copy done by one who could imitate Rizal’s handwriting while the original (almost eaten by termites) was kept by some friars. Both the Archbishop and Fr. Pi acted innocently because they did not distinguish between the genuine and the imitation of Rizal’s handwriting.

source: http://joserizal.ph/

Introduction

This section presents contrasting views on the retraction by biographers of Rizal. The team deemed it proper to present the views in the exact words of the scholars so as to avoid misinterpretations.

Read on and judge for yourself whether Rizal retracted or not.

Texts of Rizal's Retraction

The "original" discovered by Fr. Manuel Garcia, C.M. on May 18, 1935

Me declaro catolica y en esta Religion en que naci y me eduque quiero vivir y morir.

Me retracto de todo corazon de cuanto en mis palabras, escritos, inpresos y conducta ha habido contrario a mi cualidad de hijo de la Iglesia Catolica. Creo y profeso cuanto ella enseña y me somento a cuanto ella manda. Abomino de la Masonaria, como enigma que es de la Iglesia, y como Sociedad prohibida por la Iglesia. Puede el Prelado Diocesano, como Autoridad Superior Eclesiastica hacer publica esta manifastacion espontanea mia para reparar el escandalo que mis actos hayan podido causar y para que Dios y los hombers me perdonen.

Manila 29 de Deciembre de 1896

Jose Rizal

Jefe del Piquete

Juan del Fresno

Ayudante de Plaza

Eloy Moure

Translation (English)

I declare myself a catholic and in this Religion in which I was born and educated I wish to live and die.

I retract with all my heart whatever in my words, writings, publications and conduct has been contrary to my character as son of the Catholic Church. I believe and I confess whatever she teaches and I submit to whatever she demands. I abominate Masonry, as the enemy which is of the Church, and as a Society prohibited by the Church. The Diocesan Prelate may, as the Superior Ecclesiastical Authority, make public this spontaneous manifestation of mine in order to repair the scandal which my acts may have caused and so that God and people may pardon me.

Manila 29 of December of 1896

Jose Rizal

La Voz Española, December 30, 1896

Me declaro catolica y en esta Religion en que naci y me eduque quiero vivir y morir.

Me retracto de todo corazon de cuanto en mis palabras, escritos, inpresos y conducta ha habido contrario a mis cualidades de hijo de la Iglesia Catolica. Creo y profeso cuanto ella enseña y me somento a cuanto ella manda. Abomino de la Masonaria, como enigma que es de la Iglesia y como sociedad prohibida por la Iglesia. Puede el Prelado Diocesano, como autoridad superior eclesiastica hacer publica esta manifastacion espontanea para reparar el escandalo que mis actos hayan podido causar y para que Dios y los hombers me perdonen.

Manila, 29 de Diciembre de

1896-Jose Rizal

Jefe del Piquete

Juan del Fresno

Ayudante de Plaza

Eloy Moure

Fr. Balaguer's text, January 1897

Me declaro catolica y en esta Religion en que naci y me eduque quiero vivir y morir. Me retracto de todo corazon de cuanto en mis palabras, escritos, inpresos y conducta ha habido contrario a mi calidad de hijo de la Iglesia. Creo y profeso cuanto ella enseña y me somento a cuanto Ella manda. Abomino de la Masonaria, como enigma que es de la Iglesia, y como Sociedad prohibida por la misma Iglesia.

Puede el Prelado diocesano, como Autoridad superior eclesiastica hacer publica esta manifastacion espontanea mia, para reparar el escandalo que mis actos hayan podido causar, y para que Dios y los hombers me perdonen.

Manila, 29 de Diciembre de

1896-Jose Rizal

ANALYSIS OF RIZAL'S RETRACTION

At least four texts of Rizal’s retraction have surfaced. The fourth text appeared in El Imparcial on the day after Rizal’s execution; it is the short formula of the retraction.

The first text was published in La Voz Española and Diaro de Manila on the very day of Rizal’s execution, Dec. 30, 1896. The second text appeared in Barcelona, Spain, on February 14, 1897, in the fortnightly magazine in La Juventud; it came from an anonymous writer who revealed himself fourteen years later as Fr. Balaguer. The "original" text was discovered in the archdiocesan archives on May 18, 1935, after it disappeared for thirty-nine years from the afternoon of the day when Rizal was shot.

We know not that reproductions of the lost original had been made by a copyist who could imitate Rizal’s handwriting. This fact is revealed by Fr. Balaguer himself who, in his letter to his former superior Fr. Pio Pi in 1910, said that he had received "an exact copy of the retraction written and signed by Rizal. The handwriting of this copy I don’t know nor do I remember whose it is. . ." He proceeded: "I even suspect that it might have been written by Rizal himself. I am sending it to you that you may . . . verify whether it might be of Rizal himself . . . ." Fr. Pi was not able to verify it in his sworn statement.

This "exact" copy had been received by Fr. Balaguer in the evening immediately preceding Rizal’s execution, Rizal y su Obra, and was followed by Sr. W. Retana in his biography of Rizal, Vida y Escritos del Jose Rizal with the addition of the names of the witnesses taken from the texts of the retraction in the Manila newspapers. Fr. Pi’s copy of Rizal’s retraction has the same text as that of Fr. Balaguer’s "exact" copy but follows the paragraphing of the texts of Rizal’s retraction in the Manila newspapers.

Regarding the "original" text, no one claimed to have seen it, except the publishers of La Voz Espanola. That newspaper reported: "Still more; we have seen and read his (Rizal’s) own hand-written retraction which he sent to our dear and venerable Archbishop…" On the other hand, Manila pharmacist F. Stahl wrote in a letter: "besides, nobody has seen this written declaration, in spite of the fact that quite a number of people would want to see it. "For example, not only Rizal’s family but also the correspondents in Manila of the newspapers in Madrid, Don Manuel Alhama of El Imparcial and Sr. Santiago Mataix of El Heraldo, were not able to see the hand-written retraction.

Neither Fr. Pi nor His Grace the Archbishop ascertained whether Rizal himself was the one who wrote and signed the retraction. (Ascertaining the document was necessary because it was possible for one who could imitate Rizal’s handwriting aforesaid holograph; and keeping a copy of the same for our archives, I myself delivered it personally that the same morning to His Grace Archbishop… His Grace testified: At once the undersigned entrusted this holograph to Rev. Thomas Gonzales Feijoo, secretary of the Chancery." After that, the documents could not be seen by those who wanted to examine it and was finally considered lost after efforts to look for it proved futile.

On May 18, 1935, the lost "original" document of Rizal’s retraction was discovered by the archdeocean archivist Fr. Manuel Garcia, C.M. The discovery, instead of ending doubts about Rizal’s retraction, has in fact encouraged it because the newly discovered text retraction differs significantly from the text found in the Jesuits’ and the Archbishop’s copies. And, the fact that the texts of the retraction which appeared in the Manila newspapers could be shown to be the exact copies of the "original" but only imitations of it. This means that the friars who controlled the press in Manila (for example, La Voz Española) had the "original" while the Jesuits had only the imitations.

We now proceed to show the significant differences between the "original" and the Manila newspapers texts of the retraction on the one hand and the text s of the copies of Fr. Balaguer and F5r. Pio Pi on the other hand.

First, instead of the words "mi cualidad" (with "u") which appear in the original and the newspaper texts, the Jesuits’ copies have "mi calidad" (without "u").

Second, the Jesuits’ copies of the retraction omit the word "Catolica" after the first "Iglesias" which are found in the original and the newspaper texts.

Third, the Jesuits’ copies of the retraction add before the third "Iglesias" the word "misma" which is not found in the original and the newspaper texts of the retraction.

Fourth, with regards to paragraphing which immediately strikes the eye of the critical reader, Fr. Balaguer’s text does not begin the second paragraph until the fifth sentences while the original and the newspaper copies start the second paragraph immediately with the second sentences.

Fifth, whereas the texts of the retraction in the original and in the manila newspapers have only four commas, the text of Fr. Balaguer’s copy has eleven commas.

Sixth, the most important of all, Fr. Balaguer’s copy did not have the names of the witnesses from the texts of the newspapers in Manila.

In his notarized testimony twenty years later, Fr. Balaguer finally named the witnesses. He said "This . . .retraction was signed together with Dr. Rizal by Señor Fresno, Chief of the Picket, and Señor Moure, Adjutant of the Plaza." However, the proceeding quotation only proves itself to be an addition to the original. Moreover, in his letter to Fr. Pi in 1910, Fr. Balaguer said that he had the "exact" copy of the retraction, which was signed by Rizal, but her made no mention of the witnesses. In his accounts too, no witnesses signed the retraction.

How did Fr. Balaguer obtain his copy of Rizal’s retraction? Fr. Balaguer never alluded to having himself made a copy of the retraction although he claimed that the Archbishop prepared a long formula of the retraction and Fr. Pi a short formula. In Fr. Balaguer’s earliest account, it is not yet clear whether Fr. Balaguer was using the long formula of nor no formula in dictating to Rizal what to write. According to Fr. Pi, in his own account of Rizal’s conversion in 1909, Fr. Balaguer dictated from Fr. Pi’s short formula previously approved by the Archbishop. In his letter to Fr. Pi in 1910, Fr. Balaguer admitted that he dictated to Rizal the short formula prepared by Fr. Pi; however; he contradicts himself when he revealed that the "exact" copy came from the Archbishop. The only copy, which Fr. Balaguer wrote, is the one that appeared ion his earliest account of Rizal’s retraction.

Where did Fr. Balaguer’s "exact" copy come from? We do not need long arguments to answer this question, because Fr. Balaguer himself has unwittingly answered this question. He said in his letter to Fr. Pi in 1910:

"…I preserved in my keeping and am sending to you the original texts of the two formulas of retraction, which they (You) gave me; that from you and that of the Archbishop, and the first with the changes which they (that is, you) made; and the other the exact copy of the retraction written and signed by Rizal. The handwriting of this copy I don’t know nor do I remember whose it is, and I even suspect that it might have been written by Rizal himself."

In his own word quoted above, Fr. Balaguer said that he received two original texts of the retraction. The first, which came from Fr. Pi, contained "the changes which You (Fr. Pi) made"; the other, which is "that of the Archbishop" was "the exact copy of the retraction written and signed by Rizal" (underscoring supplied). Fr. Balaguer said that the "exact copy" was "written and signed by Rizal" but he did not say "written and signed by Rizal and himself" (the absence of the reflexive pronoun "himself" could mean that another person-the copyist-did not). He only "suspected" that "Rizal himself" much as Fr. Balaguer did "not know nor ... remember" whose handwriting it was.

Thus, according to Fr. Balaguer, the "exact copy" came from the Archbishop! He called it "exact" because, not having seen the original himself, he was made to believe that it was the one that faithfully reproduced the original in comparison to that of Fr. Pi in which "changes" (that is, where deviated from the "exact" copy) had been made. Actually, the difference between that of the Archbishop (the "exact" copy) and that of Fr. Pi (with "changes") is that the latter was "shorter" be cause it omitted certain phrases found in the former so that, as Fr. Pi had fervently hoped, Rizal would sign it.

According to Fr. Pi, Rizal rejected the long formula so that Fr. Balaguer had to dictate from the short formula of Fr. Pi. Allegedly, Rizal wrote down what was dictated to him but he insisted on adding the phrases "in which I was born and educated" and "[Masonary]" as the enemy that is of the Church" – the first of which Rizal would have regarded as unnecessary and the second as downright contrary to his spirit. However, what actually would have happened, if we are to believe the fictitious account, was that Rizal’s addition of the phrases was the retoration of the phrases found in the original which had been omitted in Fr. Pi’s short formula.

The "exact" copy was shown to the military men guarding in Fort Santiago to convince them that Rizal had retracted. Someone read it aloud in the hearing of Capt. Dominguez, who claimed in his "Notes’ that Rizal read aloud his retraction. However, his copy of the retraction proved him wrong because its text (with "u") and omits the word "Catolica" as in Fr. Balaguer’s copy but which are not the case in the original. Capt. Dominguez never claimed to have seen the retraction: he only "heard".

The truth is that, almost two years before his execution, Rizal had written a retraction in Dapitan. Very early in 1895, Josephine Bracken came to Dapitan with her adopted father who wanted to be cured of his blindness by Dr. Rizal; their guide was Manuela Orlac, who was agent and a mistress of a friar. Rizal fell in love with Josephine and wanted to marry her canonically but he was required to sign a profession of faith and to write retraction, which had to be approved by the Bishop of Cebu. "Spanish law had established civil marriage in the Philippines," Prof. Craig wrote, but the local government had not provided any way for people to avail themselves of the right..."

In order to marry Josephine, Rizal wrote with the help of a priest a form of retraction to be approved by the Bishop of Cebu. This incident was revealed by Fr. Antonio Obach to his friend Prof. Austin Craig who wrote down in 1912 what the priest had told him; "The document (the retraction), inclosed with the priest’s letter, was ready for the mail when Rizal came hurrying I to reclaim it." Rizal realized (perhaps, rather late) that he had written and given to a priest what the friars had been trying by all means to get from him.

Neither the Archbishop nor Fr. Pi saw the original document of retraction. What they was saw a copy done by one who could imitate Rizal’s handwriting while the original (almost eaten by termites) was kept by some friars. Both the Archbishop and Fr. Pi acted innocently because they did not distinguish between the genuine and the imitation of Rizal’s handwriting.

source: http://joserizal.ph/

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

THE MARTYRDOM OF RIZAL --- (FINALs COVERAGE included)

CLICK THE PICTURES FOR BIGGER VIEW.

One of the members of the FIRING SQUAD - THE MAGALLANES, aiming the TARGET!

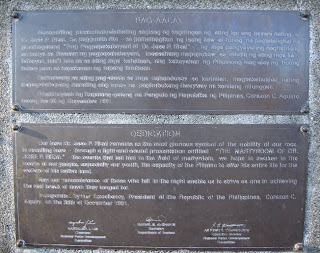

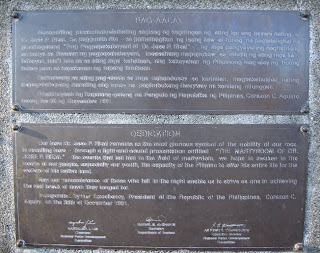

DEDICATION marker.

The execution site.

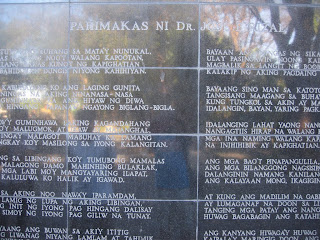

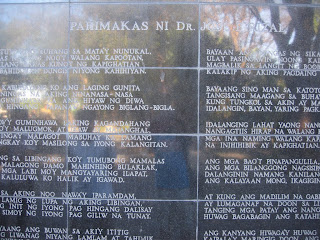

The Tagalog version.

Beside the entrance to the LIGHT and SOUND "museum" of Rizal's execution. Showing at 7pm everyday except Tuesdays.

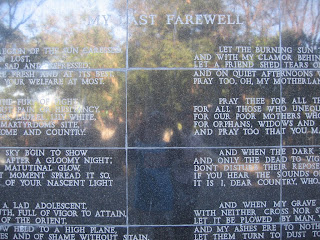

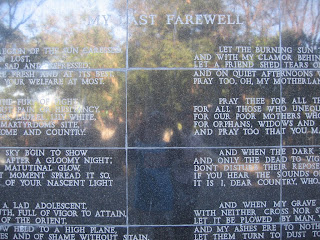

On the left wall of the "museum", carved on marble tiles is the originally untitled last poem by Rizal.

The English translation.

A poem wriiten by Andres Bonifacio himself dedicated to Rizal.

RELIEFS on Rizal's life, profession and contributions to society.

8-man Squad of Filipino Riflemen from the 70th Infantry Regiment: THE MAGALLANES

CONSUMMATUM EST (it is finished): The COMPLETION of a MARTYRDOM!

The RIZAL monument: built near the execution site of Bagumbayan, now Luneta.

Two guards in the post.

One of the members of the FIRING SQUAD - THE MAGALLANES, aiming the TARGET!

DEDICATION marker.

The execution site.

The Tagalog version.

Beside the entrance to the LIGHT and SOUND "museum" of Rizal's execution. Showing at 7pm everyday except Tuesdays.

On the left wall of the "museum", carved on marble tiles is the originally untitled last poem by Rizal.

The English translation.

A poem wriiten by Andres Bonifacio himself dedicated to Rizal.

RELIEFS on Rizal's life, profession and contributions to society.

8-man Squad of Filipino Riflemen from the 70th Infantry Regiment: THE MAGALLANES

CONSUMMATUM EST (it is finished): The COMPLETION of a MARTYRDOM!

The RIZAL monument: built near the execution site of Bagumbayan, now Luneta.

Two guards in the post.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

EL FILIBUSTERISMO

source: http://joserizal.ph

The word "filibustero" wrote Rizal to his friend, Ferdinand Blumentritt, is very little known in the Philippines. The masses do not know it yet.

Jose Alejandro, one of the new Filipinos who had been quite intimate with Rizal, said, "in writing the Noli Rizal signed his own death warrant." Subsequent events, after the fate of the Noli was sealed by the Spanish authorities, prompted Rizal to write the continuation of his first novel. He confessed, however, that regretted very much having killed Elias instead of Ibarra, reasoning that when he published the Noli his health was very much broken, and was very unsure of being able to write the continuation and speak of a revolution.

Explaining to Marcelo H. del Pilar his inability to contribute articles to the La Solidaridad, Rizal said that he was haunted by certain sad presentiments, and that he had been dreaming almost every night of dead relatives and friends a few days before his 29th birthday, that is why he wanted to finish the second part of the Noli at all costs.

Consequently, as expected of a determined character, Rizal apparently went in writing, for to his friend, Blumentritt, he wrote on March 29, 1891: "I have finished my book. Ah! I’ve not written it with any idea of vengeance against my enemies, but only for the good of those who suffer and for the rights of Tagalog humanity, although brown and not good-looking."

To a Filipino friend in Hong Kong, Jose Basa, Rizal likewise eagerly announced the completion of his second novel. Having moved to Ghent to have the book published at cheaper cost, Rizal once more wrote his friend, Basa, in Hongkong on July 9, 1891: "I am not sailing at once, because I am now printing the second part of the Noli here, as you may see from the enclosed pages. I prefer to publish it in some other way before leaving Europe, for it seemed to me a pity not to do so. For the past three months I have not received a single centavo, so I have pawned all that I have in order to publish this book. I will continue publishing it as long as I can; and when there is nothing to pawn I will stop and return to be at your side."

Inevitably, Rizal’s next letter to Basa contained the tragic news of the suspension of the printing of the sequel to his first novel due to lack of funds, forcing him to stop and leave the book half-way. "It is a pity," he wrote Basa, "because it seems to me that this second part is more important than the first, and if I do not finish it here, it will never be finished."

Fortunately, Rizal was not to remain in despair for long. A compatriot, Valentin Ventura, learned of Rizal’s predicament. He offered him financial assistance. Even then Rizal’s was forced to shorten the novel quite drastically, leaving only thirty-eight chapters compared to the sixty-four chapters of the first novel.

Rizal moved to Ghent, and writes Jose Alejandro. The sequel to Rizal’s Noli came off the press by the middle of September, 1891.On the 18th he sent Basa two copies, and Valentin Ventura the original manuscript and an autographed printed copy.

Inspired by what the word filibustero connoted in relation to the circumstances obtaining in his time, and his spirits dampened by the tragic execution of the three martyred priests, Rizal aptly titled the second part of the Noli Me Tangere, El Filibusterismo. In veneration of the three priests, he dedicated the book to them.

"To the memory of the priests, Don Mariano Gomez (85 years old), Don Jose Burgos (30 years old), and Don Jacinto Zamora (35 years old). Executed in the Bagumbayan Field on the 28th of February, 1872."

"The church, by refusing to degrade you, has placed in doubt the crime that has been imputed to you; the Government, by surrounding your trials with mystery and shadows causes the belief that there was some error, committed in fatal moments; and all the Philippines, by worshipping your memory and calling you martyrs, in no sense recognizes your culpability. In so far, therefore, as your complicity in the Cavite Mutiny is not clearly proved, as you may or may not have been patriots, and as you may or may not cherished sentiments for justice and for liberty, I have the right to dedicate my work to you as victims of the evil which I undertake to combat. And while we await expectantly upon Spain some day to restore your good name and cease to be answerable for your death, let these pages serve as a tardy wreath of dried leaves over one who without clear proofs attacks your memory stains his hands in your blood."

Rizal’s memory seemed to have failed him, though, for Father Gomez was then 73 not 85, Father Burgos 35 not 30 Father Zamora 37 not 35; and the date of execution 17th not 28th.

The FOREWORD of the Fili was addressed to his beloved countrymen, thus:

"TO THE FILIPINO PEOPLE AND THEIR GOVERNMENT"

El Filibusterismo: Mga Tauhan

Ang nobelang "El Filibusterismo" ay isinulat ng ating magiting na bayaning si Dr. Jose Rizal na buong pusong inalay sa tatlong paring martir, na lalong kilala sa bansag na GOMBURZA - Gomez, Burgos, Zamora.

Tulad ng "Noli Me Tangere", ang may-akda ay dumanas ng hirap habang isinusulat ito. Sinimulan niyang isulat ito sa London, Inglatera noong 1890 at ang malaking bahagi nito ay naisulat niya sa Bruselas, Belgica. Natapos ang kanyang akda noong Marso 29, 1891. Isang Nagngangalang Valentin Viola na isa niyang kaibigan ang nagpahiram ng pera sa kanya upang maipalimbag ang aklat noong Setyembre 22, 1891.

Ang nasabing nobela ay pampulitika na nagpapadama, nagpapahiwatig at nagpapagising pang lalo sa maalab na hangaring makapagtamo ng tunay na kalayaan at karapatan ang bayan.

Mga Tauhan:

Simoun

Ang mapagpanggap na mag-aalahas na nakasalaming may kulay

Isagani

Ang makatang kasintahan ni Paulita

Basilio

Ang mag-aaral ng medisina at kasintahan ni Juli

Kabesang Tales

Ang naghahangad ng karapatan sa pagmamay- ari ng lupang sinasaka na inaangkin ng mga prayle

Tandang Selo

Ama ni Kabesang Tales na nabaril ng kanyang sariling apo

Ginoong Pasta

Ang tagapayo ng mga prayle sa mga suliraning legal

Ben-zayb

Ang mamamahayag sa pahayagan

Placido Penitente

Ang mag-aaral na nawalan ng ganang mag-aral sanhi ng suliraning pampaaralan

Padre Camorra

Ang mukhang artilyerong pari

Padre Fernandez

Ang paring Dominikong may malayang paninindigan

Padre Florentino

Ang amain ni Isagani

Don Custodio

Ang kilala sa tawag na Buena Tinta

Padre Irene

Ang kaanib ng mga kabataan sa pagtatatag ng Akademya ng Wikang Kastila

Juanito Pelaez

Ang mag-aaral na kinagigiliwan ng mga propesor; nabibilang sa kilalang angkang may dugong Kastila

Makaraig

Ang mayamang mag-aaral na masigasig na nakikipaglaban para sa pagtatatag ng Akademya ng Wikang Kastila ngunit biglang nawala sa oras ng kagipitan.

Sandoval

Ang kawaning Kastila na sang-ayon o panig sa ipinaglalaban ng mga mag-aaral

Donya Victorina

Ang mapagpanggap na isang Europea ngunit isa namang Pilipina; tiyahin ni Paulita

Paulita Gomez

Kasintahan ni Isagani ngunit nagpakasal kay Juanito Pelaez

Quiroga

Isang mangangalakal na Intsik na nais magkaroon ng konsulado sa Pilipinas

Juli

Anak ni Kabesang Tales at katipan naman ni Basilio

Hermana Bali

Naghimok kay Juli upang humingi ng tulong kay Padre Camorra

Hermana Penchang

Ang mayaman at madasaling babae na pinaglilingkuran ni Juli

Ginoong Leeds

Ang misteryosong Amerikanong nagtatanghal sa perya

Imuthis

Ang mahiwagang ulo sa palabas ni G. Leeds

The word "filibustero" wrote Rizal to his friend, Ferdinand Blumentritt, is very little known in the Philippines. The masses do not know it yet.

Jose Alejandro, one of the new Filipinos who had been quite intimate with Rizal, said, "in writing the Noli Rizal signed his own death warrant." Subsequent events, after the fate of the Noli was sealed by the Spanish authorities, prompted Rizal to write the continuation of his first novel. He confessed, however, that regretted very much having killed Elias instead of Ibarra, reasoning that when he published the Noli his health was very much broken, and was very unsure of being able to write the continuation and speak of a revolution.

Explaining to Marcelo H. del Pilar his inability to contribute articles to the La Solidaridad, Rizal said that he was haunted by certain sad presentiments, and that he had been dreaming almost every night of dead relatives and friends a few days before his 29th birthday, that is why he wanted to finish the second part of the Noli at all costs.

Consequently, as expected of a determined character, Rizal apparently went in writing, for to his friend, Blumentritt, he wrote on March 29, 1891: "I have finished my book. Ah! I’ve not written it with any idea of vengeance against my enemies, but only for the good of those who suffer and for the rights of Tagalog humanity, although brown and not good-looking."

To a Filipino friend in Hong Kong, Jose Basa, Rizal likewise eagerly announced the completion of his second novel. Having moved to Ghent to have the book published at cheaper cost, Rizal once more wrote his friend, Basa, in Hongkong on July 9, 1891: "I am not sailing at once, because I am now printing the second part of the Noli here, as you may see from the enclosed pages. I prefer to publish it in some other way before leaving Europe, for it seemed to me a pity not to do so. For the past three months I have not received a single centavo, so I have pawned all that I have in order to publish this book. I will continue publishing it as long as I can; and when there is nothing to pawn I will stop and return to be at your side."

Inevitably, Rizal’s next letter to Basa contained the tragic news of the suspension of the printing of the sequel to his first novel due to lack of funds, forcing him to stop and leave the book half-way. "It is a pity," he wrote Basa, "because it seems to me that this second part is more important than the first, and if I do not finish it here, it will never be finished."

Fortunately, Rizal was not to remain in despair for long. A compatriot, Valentin Ventura, learned of Rizal’s predicament. He offered him financial assistance. Even then Rizal’s was forced to shorten the novel quite drastically, leaving only thirty-eight chapters compared to the sixty-four chapters of the first novel.

Rizal moved to Ghent, and writes Jose Alejandro. The sequel to Rizal’s Noli came off the press by the middle of September, 1891.On the 18th he sent Basa two copies, and Valentin Ventura the original manuscript and an autographed printed copy.

Inspired by what the word filibustero connoted in relation to the circumstances obtaining in his time, and his spirits dampened by the tragic execution of the three martyred priests, Rizal aptly titled the second part of the Noli Me Tangere, El Filibusterismo. In veneration of the three priests, he dedicated the book to them.

"To the memory of the priests, Don Mariano Gomez (85 years old), Don Jose Burgos (30 years old), and Don Jacinto Zamora (35 years old). Executed in the Bagumbayan Field on the 28th of February, 1872."

"The church, by refusing to degrade you, has placed in doubt the crime that has been imputed to you; the Government, by surrounding your trials with mystery and shadows causes the belief that there was some error, committed in fatal moments; and all the Philippines, by worshipping your memory and calling you martyrs, in no sense recognizes your culpability. In so far, therefore, as your complicity in the Cavite Mutiny is not clearly proved, as you may or may not have been patriots, and as you may or may not cherished sentiments for justice and for liberty, I have the right to dedicate my work to you as victims of the evil which I undertake to combat. And while we await expectantly upon Spain some day to restore your good name and cease to be answerable for your death, let these pages serve as a tardy wreath of dried leaves over one who without clear proofs attacks your memory stains his hands in your blood."

Rizal’s memory seemed to have failed him, though, for Father Gomez was then 73 not 85, Father Burgos 35 not 30 Father Zamora 37 not 35; and the date of execution 17th not 28th.

The FOREWORD of the Fili was addressed to his beloved countrymen, thus:

"TO THE FILIPINO PEOPLE AND THEIR GOVERNMENT"

El Filibusterismo: Mga Tauhan

Ang nobelang "El Filibusterismo" ay isinulat ng ating magiting na bayaning si Dr. Jose Rizal na buong pusong inalay sa tatlong paring martir, na lalong kilala sa bansag na GOMBURZA - Gomez, Burgos, Zamora.

Tulad ng "Noli Me Tangere", ang may-akda ay dumanas ng hirap habang isinusulat ito. Sinimulan niyang isulat ito sa London, Inglatera noong 1890 at ang malaking bahagi nito ay naisulat niya sa Bruselas, Belgica. Natapos ang kanyang akda noong Marso 29, 1891. Isang Nagngangalang Valentin Viola na isa niyang kaibigan ang nagpahiram ng pera sa kanya upang maipalimbag ang aklat noong Setyembre 22, 1891.

Ang nasabing nobela ay pampulitika na nagpapadama, nagpapahiwatig at nagpapagising pang lalo sa maalab na hangaring makapagtamo ng tunay na kalayaan at karapatan ang bayan.

Mga Tauhan:

Simoun

Ang mapagpanggap na mag-aalahas na nakasalaming may kulay

Isagani

Ang makatang kasintahan ni Paulita

Basilio

Ang mag-aaral ng medisina at kasintahan ni Juli

Kabesang Tales

Ang naghahangad ng karapatan sa pagmamay- ari ng lupang sinasaka na inaangkin ng mga prayle

Tandang Selo

Ama ni Kabesang Tales na nabaril ng kanyang sariling apo

Ginoong Pasta

Ang tagapayo ng mga prayle sa mga suliraning legal

Ben-zayb

Ang mamamahayag sa pahayagan

Placido Penitente

Ang mag-aaral na nawalan ng ganang mag-aral sanhi ng suliraning pampaaralan

Padre Camorra

Ang mukhang artilyerong pari

Padre Fernandez

Ang paring Dominikong may malayang paninindigan

Padre Florentino

Ang amain ni Isagani

Don Custodio

Ang kilala sa tawag na Buena Tinta

Padre Irene

Ang kaanib ng mga kabataan sa pagtatatag ng Akademya ng Wikang Kastila

Juanito Pelaez

Ang mag-aaral na kinagigiliwan ng mga propesor; nabibilang sa kilalang angkang may dugong Kastila

Makaraig

Ang mayamang mag-aaral na masigasig na nakikipaglaban para sa pagtatatag ng Akademya ng Wikang Kastila ngunit biglang nawala sa oras ng kagipitan.

Sandoval

Ang kawaning Kastila na sang-ayon o panig sa ipinaglalaban ng mga mag-aaral

Donya Victorina

Ang mapagpanggap na isang Europea ngunit isa namang Pilipina; tiyahin ni Paulita

Paulita Gomez

Kasintahan ni Isagani ngunit nagpakasal kay Juanito Pelaez

Quiroga

Isang mangangalakal na Intsik na nais magkaroon ng konsulado sa Pilipinas

Juli

Anak ni Kabesang Tales at katipan naman ni Basilio

Hermana Bali

Naghimok kay Juli upang humingi ng tulong kay Padre Camorra

Hermana Penchang

Ang mayaman at madasaling babae na pinaglilingkuran ni Juli

Ginoong Leeds

Ang misteryosong Amerikanong nagtatanghal sa perya

Imuthis

Ang mahiwagang ulo sa palabas ni G. Leeds

Monday, February 1, 2010

RIZAL'S PHILOSOPHIES

Philosophies in Life

PHILOSOPHY may be defined as the study and pursuit of facts which deal with the ultimate reality or causes of things as they affect life.

The philosophy of a country like the Philippines is made up of the intricate and composite interrelationship of the life histories of its people; in other word, the philosophy of our nation would be strange and undefinable if we do not delve into the past tied up with the notable life experiences of the representative personalities of our nation.

Being one of the prominent representatives of Filipino personalities, Jose Rizal is a fit subject whose life philosophy deserves to be recognized.

Having been a victim of Spanish brutality early in his life in Calamba, Rizal had thus already formed the nucleus of an unfavorable opinion of Castillian imperialistic administration of his country and people.

Pitiful social conditions existed in the Philippines as late as three centuries after his conquest in Spain, with agriculture, commerce, communications and education languishing under its most backward state. It was because of this social malady that social evils like inferiority complex, cowardice, timidity and false pride pervaded nationally and contributed to the decay of social life. This stimulated and shaped Rizal’s life phylosophy to be to contain if not eliminate these social ills.

Educational Philosophy

Rizal’s concept of the importance of education is clearly enunciated in his work entitled Instruction wherein he sought improvements in the schools and in the methods of teaching. He maintained that the backwardness of his country during the Spanish ear was not due to the Filipinos’ indifference, apathy or indolence as claimed by the rulers, but to the neglect of the Spanish authorities in the islands. For Rizal, the mission of education is to elevate the country to the highest seat of glory and to develop the people’s mentality. Since education is the foundation of society and a prerequisite for social progress, Rizal claimed that only through education could the country be saved from domination.

Rizal’s philosophy of education, therefore, centers on the provision of proper motivation in order to bolster the great social forces that make education a success, to create in the youth an innate desire to cultivate his intelligence and give him life eternal.

Religious Philosophy

Rizal grew up nurtured by a closely-knit Catholic family, was educated in the foremost Catholic schools of the period in the elementary, secondary and college levels; logically, therefore, he should have been a propagator of strictly Catholic traditions. However, in later life, he developed a life philosophy of a different nature, a philosophy of a different Catholic practice intermingled with the use of Truth and Reason.

Why the change?

It could have been the result of contemporary contact, companionship, observation, research and the possession of an independent spirit.Being a critical observer, a profound thinker and a zealous reformer, Rizal did not agree with the prevailing Christian propagation of the Faith by fire and sword. This is shown in his Annotation of Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas.

Rizal did not believe in the Catholic dogma that salvation was only for Catholics and that outside Christianity, salvation was not possible even if Catholics composed only a small minority of the world’s religious groups. Nor did he believe in the Catholic observation of fasting as a sacrifice, nor in the sale of such religious items as the cross, medals, rosaries and the like in order to propagate the Faith and raise church funds. He also lambasted the superstitious beliefs propagated by the priests in the church and in the schools. All of these and a lot more are evidences of Rizal’s religious philosophy.

Political Philosophy

In Rizal’s political view, a conquered country like the Philippines should not be taken advantage of but rather should be developed, civilized, educated and trained in the science of self-government.

He bitterly assailed and criticized in publications the apparent backwardness of the Spanish ruler’s method of governing the country which resulted in:

1. the bondage and slavery of the conquered ;

2. the Spanish government’s requirement of forced labor and force military service upon the n natives;

3. the abuse of power by means of exploitation;

4. the government ruling that any complaint against the authorities was criminal; and

5. Making the people ignorant, destitute and fanatic, thus discouraging the formation of a national sentiment.

Rizal’s guiding political philosophy proved to be the study and application of reforms, the extension of human rights, the training for self government and the arousing of spirit of discontent over oppression, brutality, inhumanity, sensitiveness and self love.

Ethical Philosophy

The study of human behavior as to whether it is good or bad or whether it is right or wrong is that science upon which Rizal’s ethical philosophy was based. The fact that the Philippines was under Spanish domination during Rizal’s time led him to subordinate his philosophy to moral problems. This trend was much more needed at that time because the Spaniards and the Filipinos had different and sometimes conflicting morals. The moral status of the Philippines during this period was one with a lack of freedom, one with predominance of foreign masters, one with an imposition of foreign religious worship, devotion, homage and racial habits. This led to moral confusion among the people, what with justice being stifled, limited or curtailed and the people not enjoying any individual rights.

To bolster his ethical philosophy, Dr. Rizal had recognized not only the forces of good and evil, but also the tendencies towards good and evil. As a result, he made use of the practical method of appealing to the better nature of the conquerors and of offering useful methods of solving the moral problems of the conquered.

To support his ethical philosophy in life, Rizal:

1. censured the friars for abusing the advantage of their position as spiritual leaders and the ignorance and fanaticism of the natives;

2. counseled the Filipinos not to resent a defect attributed to them but to accept same as reasonable and just;

3. advised the masses that the object of marriage was the happiness and love of the couple and not financial gain;

4. censured the priests who preached greed and wrong morality; and

5. advised every one that love and respect for parents must be strictly observed.

Social Philosophy

That body of knowledge relating to society including the wisdom which man's experience in society has taught him is social philosophy. The facts dealt with are principles involved in nation building and not individual social problems. The subject matter of this social philosophy covers the problems of the whole race, with every problem having a distinct solution to bolster the people’s social knowledge.

Rizal’s social philosophy dealt with;

1. man in society;

2. influential factors in human life;

3. racial problems;

4. social constant;

5. social justice;

6. social ideal;

7. poverty and wealth;

8. reforms;

9. youth and greatness;

10. history and progress;

11. future Philippines.

The above dealt with man’s evolution and his environment, explaining for the most part human behavior and capacities like his will to live; his desire to possess happiness; the change of his mentality; the role of virtuous women in the guidance of great men; the need for elevating and inspiring mission; the duties and dictates of man’s conscience; man’s need of practicing gratitude; the necessity for consulting reliable people; his need for experience; his ability to deny; the importance of deliberation; the voluntary offer of man’s abilities and possibilities; the ability to think, aspire and strive to rise; and the proper use of hearth, brain and spirit-all of these combining to enhance the intricacies, beauty and values of human nature. All of the above served as Rizal’s guide in his continuous effort to make over his beloved Philippines.

PHILOSOPHY may be defined as the study and pursuit of facts which deal with the ultimate reality or causes of things as they affect life.

The philosophy of a country like the Philippines is made up of the intricate and composite interrelationship of the life histories of its people; in other word, the philosophy of our nation would be strange and undefinable if we do not delve into the past tied up with the notable life experiences of the representative personalities of our nation.

Being one of the prominent representatives of Filipino personalities, Jose Rizal is a fit subject whose life philosophy deserves to be recognized.

Having been a victim of Spanish brutality early in his life in Calamba, Rizal had thus already formed the nucleus of an unfavorable opinion of Castillian imperialistic administration of his country and people.

Pitiful social conditions existed in the Philippines as late as three centuries after his conquest in Spain, with agriculture, commerce, communications and education languishing under its most backward state. It was because of this social malady that social evils like inferiority complex, cowardice, timidity and false pride pervaded nationally and contributed to the decay of social life. This stimulated and shaped Rizal’s life phylosophy to be to contain if not eliminate these social ills.

Educational Philosophy

Rizal’s concept of the importance of education is clearly enunciated in his work entitled Instruction wherein he sought improvements in the schools and in the methods of teaching. He maintained that the backwardness of his country during the Spanish ear was not due to the Filipinos’ indifference, apathy or indolence as claimed by the rulers, but to the neglect of the Spanish authorities in the islands. For Rizal, the mission of education is to elevate the country to the highest seat of glory and to develop the people’s mentality. Since education is the foundation of society and a prerequisite for social progress, Rizal claimed that only through education could the country be saved from domination.

Rizal’s philosophy of education, therefore, centers on the provision of proper motivation in order to bolster the great social forces that make education a success, to create in the youth an innate desire to cultivate his intelligence and give him life eternal.

Religious Philosophy